“Technique is a chest of tools from which the skilled artisan draws what he needs at the right time for the right purpose.“

– Josef Hofmann

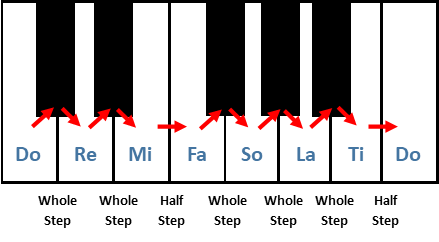

I’ve always found it handy to know specific piano techniques prior to trying to use a particular technique in a piece. Thus, I really like technical exercises that can advance my piano technique in isolation. Of course, you do also have to learn particular techniques for unique issues in pieces, but having frequently used technical skills in already in place makes learning new pieces much easier. Consequently, I urge all my students to practice some technique regularly to build up their own “technique toolbox”. Sometimes, I call this technique practice “warm-ups for playing the piano” and have my students think of technique practice as being like how athletes warm-up their body before doing their regular practice. I also like to combine technique practice with learning music theory whenever possible.

I’ve struggled in the past with deciding what skills to include in assigned technique practice. I originally started with the same technical skills list that was required for my music exams, but have substantially expanded and also reduced that list over time. I now think this technique list is an ongoing project as I figure out new skills which should be included in the list. Listed below are the current technique skills that I typically include with my lessons:

Beginning Student Technique List

| Technique Name | Resource | Comments |

| Finger Dexterity, Finger Strength, Finger Independence | Schmitt Op. 16, Nos. 1-10, The Complete Technique Book – Exercise 4i | I occasionally modify these exercises to make variations for my teaching book. |

| Beginning Drop-Roll | The Hanon Studies Book 1 – No. 1 | Introduction to Drop-Roll and wrist flexibility |

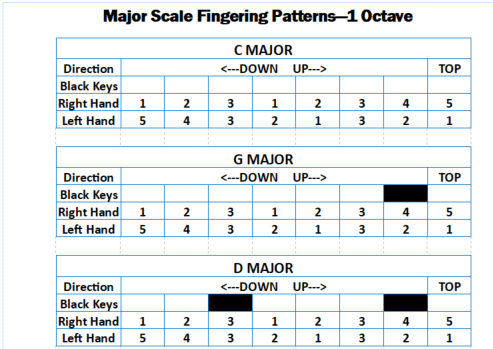

| Beginning Scales | My Teaching Book – One Octave Scales, Hands Separate | Cross-over and under, circle of fifths, key signatures |

| Two Handed Arpeggios | My Teaching Book | Move around the entire keyboard, learn basic chords, circle of fifths, use of damper pedal |

| Phrasing, Drop-Roll, Legato, Slurs | The Hanon Studies Book 1 – No. 2, 3, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 | Also has some staccato included |

| Various Staccato touches | The Hanon Studies Book 1 – No. 5, 6, 7, 8 | Wrist Staccato, portamento, marcato, forearm staccato |

| Various legato touches | The Hanon Studies Book 1 – No. 4, 9, | |

| Rotary motion | The Hanon Studies Book 1 – No. 10, A Dozen A Day Book Two – Group I No. 2, The Complete Piano Technique Book – Example 2k, 2l, 2m, 2n, A Dozen A Day Book 2 – Group II No. 4, A Dozen A Day Book 2 – Group IV No. 5 | |

| Chord Drop-Roll | Personal Teaching Book – Chord Scales | Drop-Roll, Pedal, chords available within a key |

| Legato and Staccato 3rds | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group I No. 3, Schmitt Op. 16, Nos. 119-127, A Dozen A Day Book 2 – Group I No. 11, Group IV No. 6 | Double notes |

| Finger stretch and independence | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group I Nos. 7,8 | |

| Repeated Notes | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group III No. 4 | |

| 1 Octave Scales Hands Together | The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences | Circle of Fifths, key signatures |

Intermediate Students Technique List

| Technique Name | Resource | Comments |

| Ornaments | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group III No. 10, My Teaching Book | Mordent, Appogiatura, Acciaccatura, Turn, Grace Notes |

| Trills | Hanon — The Virtuoso Pianist in 60 Exercises: Complete No. 46, Brahms 51 Exercises – No. 17, My Teaching Book | |

| Finger Dexterity | Brahms 51 Exercises – No. 39 | Good preparation for the Bach Preludes and Fugues |

| Left Hand Jumps | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group V No. 2 | |

| Staccato Double 6ths | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group V No. 5, The Manual of Scales, Broken Chords, and Arpeggios for Piano | |

| Glissandos | A Dozen A Day Book 1 – Group V No. 10 | |

| Poly Rhythms | Wendy Stevens – Polyrhythm Exercise No. 1, Brahms 51 Exercises – Nos. 1a-1d | |

| Legato Chromatic Thirds | My Teaching Book, The Manual of Scales, Broken Chords, and Arpeggios for Piano | |

| Scales – Two Octave and Four Octave, hands together, Chromatic | The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences | |

| One handed Arpeggios – Hands together, two octaves and four octaves | The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences | |

| Cadences | The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences, My Teaching Book | Include Perfect, Plagal, Interrupted, Imperfect Cadences |

| Double Octaves – staccato | The Manual of Scales, Broken Chords, and Arpeggios for Piano | |

| Thumb accents, dynamics practice, hand balance, speed work, one hand staccato – one hand legato, finger strength, dotted rhythms, different articulations | Hanon — The Virtuoso Pianist in 60 Exercises: Complete * | |

| Chromatic, Various Minor Scales | The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences, My Teaching Book | |

| 7th and diminished arpeggios + inversions | The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences | arpeggios |

| Mode Scales, Blues/Jazz Scale, Whole Note scale | My Teaching Book |

* Why I love Hanon by Dawn Taylor-May

Favorite Technique Books

The Hanon Studies Book 1 by John Thompson, published by Hal Leonard

The Complete Piano Technique Book by Jennifer Castellano, published by Fundamental Changes, ltd.

Hanon for Two, arranged by Melody Bober, published by Alfred

Schmitt Op. 16 Preparatory Exercises For the Piano, by Aloys Schmitt, published by Schirmer

The Complete Book of Scales, Chords, Arpeggios & Cadences by Willard Palmer, Morton Manus, Amanda Vick Lethco, published by Alfred

The Manual of Scales, Broken Chords, and Arpeggios for Piano, published by ABRSM

Hanon — The Virtuoso Pianist in 60 Exercises: Complete, composed by Charles-Louis Hanon, edited by Allan Small, published by Alfred

A Dozen A Day Books Prep through Book Two, by Edna-Mae Burnam, published by The Willis Music Company

My Teaching Book – I modify or specially arrange exercises for my students

Wendy Stevens Rhythm Worksheets

Brahms 51 Exercises for the Piano – by Johannes Brahms

Non-Exercise Technique Practice

Sometimes students, especially intermediate or advanced students don’t like practicing technique via exercises. In that case, I try to find pieces at the right level that include particular technique skills. I currently use the following books as a resource for practicing technique through pieces:

Tone Touch & Technique for the Young Pianist by Max Cooke, published by EMI Music Publishing

Tone Touch & Technique for the Advanced Pianist by Max Cooke, published by EMI Music Publishing

Technique through Repertoire Book 1, Edited by Christopher Madden and Jani Parsons, published by The Frances Clark Center

Technique through Repertoire Book 2, Edited by Christopher Madden and Jani Parsons, published by The Frances Clark Center